Engineered to last: Engaging industry partners to ensure long-term success

USPCASE is creating a valuable resource for Pakistan’s energy sector through its Centers for Advanced Studies in Energy at NUST and UET Peshawar.

USPCASE is creating a valuable resource for Pakistan’s energy sector through its Centers for Advanced Studies in Energy at NUST and UET Peshawar.

Engineers design solutions. It’s what they do. So, when you’re looking at an ongoing problem – the nonstop need for electric power in the modern world – you need a solution that will be as long-term as the problem itself.

That’s why the U.S.-Pakistan Centers for Advanced Studies in Energy have made industry engagement a crucial part of their operations. Industry engagement is a key strategy to ensure the sustainability of the centers.

Building a support system

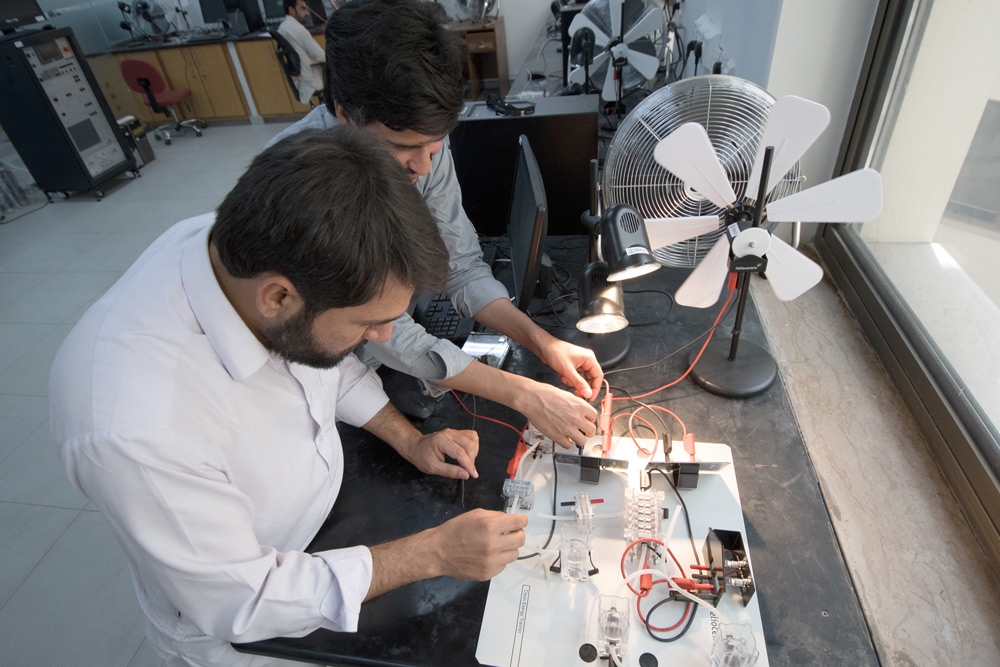

There are several components to the USPCASE industry engagement program, and they’re all designed to make the centers more valuable to the Pakistani energy sector. One element involves leveraging the infrastructure of the centers themselves, says Ammar Yassar, USPCASE corporate engagement specialist. The centers have laboratories, expert faculty and graduate students who conduct research in those labs, he explains.

“That infrastructure – facilities and services – we are offering to industry, charging money and creating revenue,” he adds.

Revenue is a fundamental goal for the centers. When the U.S. Agency for International Development first put out a call for proposals on the project, it specified that the centers should tap industry support to increase the quality of faculty at the hosting universities – the National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST) and the University of Engineering and Technology Peshawar (UET-P). The centers need to create revenue to avoid relying entirely on public or donor financing. USAID hoped the centers would become a model to strengthen higher education that could be replicated in other sectors, universities and, perhaps, nations.

Three years after inception, staffers with the USPCASE initiative have already established solid relationships with industry players. To date, there have been four stakeholder meetings in which executives and engineers from Pakistani energy companies and agencies provide input that guides the curriculum development at UET-P and NUST. “If the curriculum is aligned with industry need, there will be a good market for our graduates,” Yassar notes.

The centers also have established formal partnerships with several organizations, including the oil and gas company KPOGCL, the Pakistani Department of Sciences and Technology, Pakistan Green Building Council, the Center for Energy Research and Development, Sky Electric, Dice and Fauji Fertilizer Company Ltd.

Along with partnerships, the centers have secured contracts. For instance, center experts were hired by the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) in Pakistan, a region in the northwestern part of the country that was created in 1947 and recently merged with neighboring province Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). There, center scholars created a 10-year energy plan to help FATA secure adequate electric generation resources and strengthen the local economy.

Plus, the centers are in the process of creating facilities from which they can offer industry certifications, equipment testing, training and more.

In addition, the centers foster relationships with organizations that will give students valuable internships to equip graduates with skills desired by industry. Approximately 70 students have secured positions that enabled them to apply lessons to real-world problems.

Going with the flow

Going with the flow

The chronic shortage of electric capacity in northwestern Pakistan is a challenge. “KP province has tremendous potential electricity generation through micro-hydro turbines. However, the control of these turbines is an issue,” says Muhammad Saeed, chief executive officer of Switch Mode, a company that has been working with USPCASE UET-P to develop a frequency control mechanism for micro-hydro generators.

Micro-hydro facilities typically produce between 5 and 100 kilowatts of electricity using the natural flow of water in small streams and canals. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, even streams with a depth as shallow as 13 inches could be used for such generation.

The problem, though, is frequency, as explained by Dr. Shoaib Ahmad, who is deputy director of the SAARC Energy Centre. Established under the South Asia Association for Regional Cooperation, this organization fosters energy trade, collaboration, research and knowledge sharing among all eight SAARC nations: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

“Canals run 365 days a year, 24/7, but water is flowing with a speed that is very low … say 1.5 meters per second,” Ahmad says. This means there is no potential energy, such as that stored when water is held behind a damn. There is only kinetic energy or the energy created by motion.

With potential energy, generator operators can control the frequency of the electricity by increasing or decreasing water flow through a turbine. Since there is no such option in these systems, operators need another solution.

In Pakistan, the grid operates at a frequency of 50 hertz, notes NUST student Afshan Qamar, who worked with Saeed of Switch Mode on electronic load controllers that could stand in for water-flow-based frequency regulation. She explains that the solution she worked on put a resistive load into the micro-hydro generator that operated in parallel with the load from users of the electricity. “As the user load goes up or down, the load controller senses the frequency on the generator and when that frequency diverts from 50 hertz, the resistive load turns on and off so that the frequency remains balanced,” she says.

Other engineers have designed frequency control devices for micro-hydro generators, but they’re pricey imports, Qamar adds. “When you manufacture your own, it can be cheaper. Then more people can deploy micro-hydro,” she notes. That’s a huge benefit to northern Pakistan, a region that some say could have as much as a 300-megawatt micro-hydro potential.

How much power can individual systems produce? That was the question answered by Ihtesham Ahmad, another NUST student. He worked for the SAARC Energy Centre, where he was tasked with producing a model to estimate the energy potential of any given canal. “I devised a simple software tool to estimate total annual power generation from canals utilizing any type of microturbine,” he says. This important work was also shared with a government energy development organization.

Another student intern working for SAARC worked on finding ways to reduce the cost of small biogas plants used in rural areas. As SAARC’s Ahmad explains, a small household biogas plant that uses animal manure to generate power for cooking and groundwater irrigation pumps could easily support a family of five or six people. “But in this area, the cost of those plants was around 70,000 to 80,000 rupees,” Ahmad says. That’s prohibitively expensive for many people who would benefit from such systems, so a USPCASE intern worked on finding ways to cut that cost down below 30,000 rupees.

“Students are good foot soldiers,” says Yassar. They help organizations like the SAARC Energy Centre conduct vital research, and that research builds their value to future employers. Ihtesham Ahmad verifies that the exposure he gained by working with SAARC “helped in professional grooming.”

Internships also help students expand their problem-solving skills. “In the labs where we do projects, things work,” Qamar says. “But when you deploy your devices in the field, they face different environmental conditions. One of the main things in my mind was will it work when it is deployed on some sites, in some areas? You also think about cost – optimization with the minimal cost. These are parameters you have to consider when you make something for the market.”

Working together

Such real-world concerns are one reason SAARC’s Ahmad would like to see the USPCASE centers employ more industry participants and practitioners on the teaching staff. Fortunately, because the centers regularly solicit industry feedback, he has a chance to air this view.

Yassar, who spearheads the industry engagement part of the USPCASE program, started building industry alliances by conducting research to discover who’s who in energy in Pakistan and creating a list of potential stakeholders. Once he had some 75 names on the list, he began reaching out to people individually with very targeted communications. Some, he reached out to for feedback on the program. Some he queried about interest in research.

Others he approached for grants, consulting assignments or partnerships, such as joint research projects. And, of course, he also sought out internships for students.

This approach seems to be working because industry players show strong support for the USPCASE initiative. To date, the program has been able to raise more than $1.38 million in different sources, and an endowment fund has been established at one of the centers. More than 65 percent of center graduates have gained employment in the industry, while others have gone on to start their own companies or pursue even more education.

“The energy sector in Pakistan is in need of professionals with power electronics skills, and the USPCASE project is striving to create that critical mass,” says Saeed, who was the principal investigator on the micro-hydro frequency controller project. His praise for the program covers other factors, as well.

“The program has active involvement from the industry and energy sector. This will better prepare the students for their practical life and provide leadership to Pakistan’s energy sector. The research infrastructure that has been put in place also will be an asset for the energy sector of Pakistan.”

By Betsy Loeff